07: Sample Processing

RSTr-samples.RmdOverview

In the first series of vignettes, we worked with high-level wrapper

functions like age_standardize(),

suppress_estimates(), and get_estimates(). In

this vignette, we will be working with the functions that underlie these

wrappers and manually generating our estimates, unlocking the more

powerful capabilities of RSTr.

Before we begin, note that the above functions make direct changes to

our RSTr model object. We can manually save our estimates

to the model object, but these estimates will not be automatically

added. In exchange for more power with sample processing, we lose some

of the convenience afforded to us by these wrapper functions.

The load_samples() function

To begin, let’s generate samples for a new model:

mod_mst <- mstcar(name = "my_test_model", data = miheart, adjacency = miadj, seed = 1234)

#> Starting sampler on Batch 1 at Fri Dec 19 00:10:01

#> Generating estimates...

#> Model finished at Fri Dec 19 00:10:27The load_samples() function

Once mstcar() tells you that the model is finished

running, you can import samples into R using

load_samples(). load_samples() takes in four

arguments:

RSTr_obj: OurRSTrmodel object;param: The parameter to import samples for; andburn: Specifies a burn-in period for samples. This allows the model time to stabilize before using samples to generate estimates. By default, has a burn-in period of 2000 samples.

Any dimnames that were saved to data will

be applied to the samples as appropriate. Here, we pull in the

lambda samples for our test Michigan dataset with a

2000-sample burn-in period (as specified by the default arguments). We

also multiply by 100,000 as it is common to display mortality rates per

100,000 individuals:

samples <- load_samples(mod_mst, param = "lambda", burn = 2000) * 1e5Group aggregation

In many cases, we will want to aggregate our data across non-age

groups, such as when looking at prevalence estimates or to simply

consolidate our non-age sociodemographic groups. In our Michigan

dataset, we have 10 years of data over which we can consolidate to look

at prevalence. In these cases, we need to pull in the population array

as a weight. First, we need to check which margin contains our year

information using the dim() function:

dim(samples)

#> [1] 83 6 10 400Our samples array has four margins with dimensions

83, 6, 10, and 400,

representing the spatial regions, age groups, time periods, and

iterations, respectively. Let’s set a variable margin_time

to represent our time period margin and aggregate our

samples estimates across 1988-1988 using the

aggregate_samples() function. The population data needed to

weight our samples can be pulled from our RSTr model

object:

margin_time <- 3

pop <- mod_mst$data$n

samples_7988 <- aggregate_samples(samples, pop, margin_time)Now, we have a standalone sample array for our 1988-1988 samples. But

what if we are interested in both the individual year data and

the prevalence data? We can alternatively bind these new samples to our

main samples array by adding in values for the

bind_new and new_name arguments:

samples <- aggregate_samples(samples, pop, margin_time, bind_new = TRUE, new_name = "1979-1988")Group-aggregation is a feature unique to only samples; group-aggregation cannot be performed on model objects.

Age-standardization

The process of age-standardization is similar to that of

group-aggregation, but requires a bit more nuance in its use. We can

also use our samples to age-standardize these into a 35-64 group. Like

before, since we are using data from 1988-1988, we can use 1980 standard

populations from NIH

to generate a std_pop vector:

With std_pop generated, we need to then check which

margin contains our age group information using the dim()

function:

dim(samples)

#> [1] 83 6 11 400Our age groups lay along the second margin. Let’s set a variable

margin_age and standardize our samples

estimates across ages 35-64 using the standardize_samples()

function:

margin_age <- 2

groups <- c("35-44", "45-54", "55-64")

samples_3564 <- standardize_samples(samples, std_pop, margin_age, groups)Note that there may be times where you have groups stratified by both

age and other sociodemographic groups. In these cases, you’ll have to

refactor your sample array so that the age groups are separated from

your other groups before doing age-standardization, such as using

as.data.frame.table() in conjunction with

xtabs().

Now, we have a standalone array for our age-standardized 35-64 age

group. Similarly to aggregate_samples(), we can

alternatively consolidate this into our main samples array

by adding in values for the bind_new and

new_name arguments:

samples <- standardize_samples(

samples,

std_pop,

margin_age,

groups,

bind_new = TRUE,

new_name = "35-64"

)Now, our samples for samples are aggregated by year and

age-standardized, and we have matching array values for

pop. Note that if you plan on doing a mix of non-age

aggregation and age-standardization, do age-standardization

after aggregation, as doing age-standardization first will

alter the results of any aggregation done afterward.

Estimates and Reliability

To get our medians, we simply put our samples into get_medians():

medians <- get_medians(samples)Let’s get some reliability metrics for our dataset. First, let’s

generate our relative precisions at 95% credibility using the

get_credible_interval() and

get_relative_precision() functions, then create a

logical array that tells us which estimates

are unreliable:

ci <- get_credible_interval(sample = samples, perc_ci = 0.95)

rel_prec <- get_relative_precision(medians, ci)

low_rel_prec <- rel_prec < 1Now, let’s generate a similar logical array

for populations less than 1000 and use these criteria to create a set of

suppressed medians. A median will be suppressed if it meets either of

the two criteria. Note that since our samples are age-standardized, we

also have to extend our pop array to match in size using

the aggregate_count() function:

pop <- aggregate_count(pop, margin_age, groups = 1:3, bind_new = TRUE, new_name = "35-64")

pop <- aggregate_count(pop, margin_time, bind_new = TRUE, new_name = "1988-1988")

low_population <- pop < 1000

medians_supp <- medians

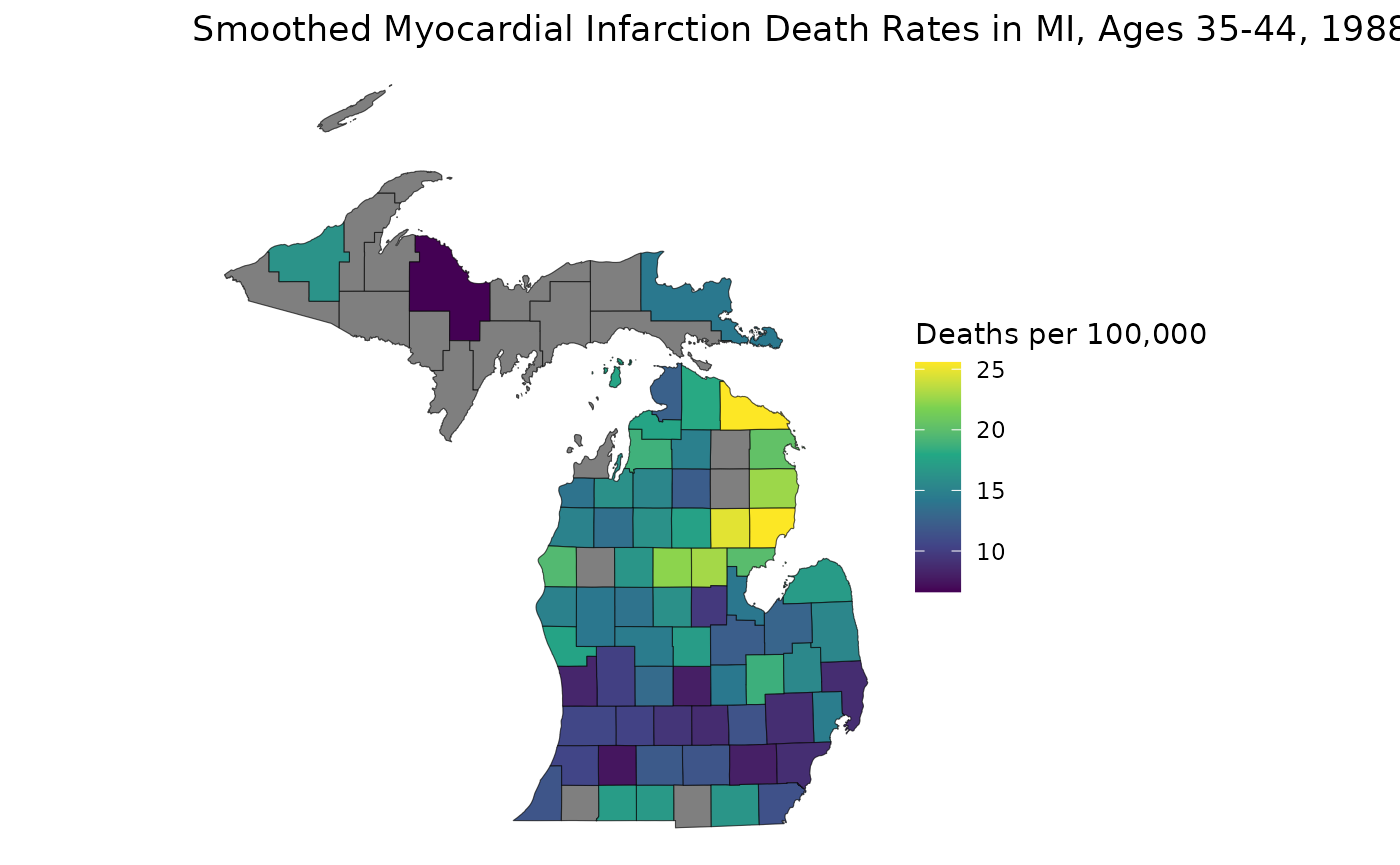

medians_supp[low_rel_prec | low_population] <- NALet’s now map our suppressed estimates:

library(ggplot2)

est_3544 <- medians_supp[, "35-44", "1988"]

ggplot(mishp) +

geom_sf(aes(fill = est_3544)) +

labs(

title = "Smoothed Myocardial Infarction Death Rates in MI, Ages 35-44, 1988",

fill = "Deaths per 100,000"

) +

scale_fill_viridis_c() +

theme_void()

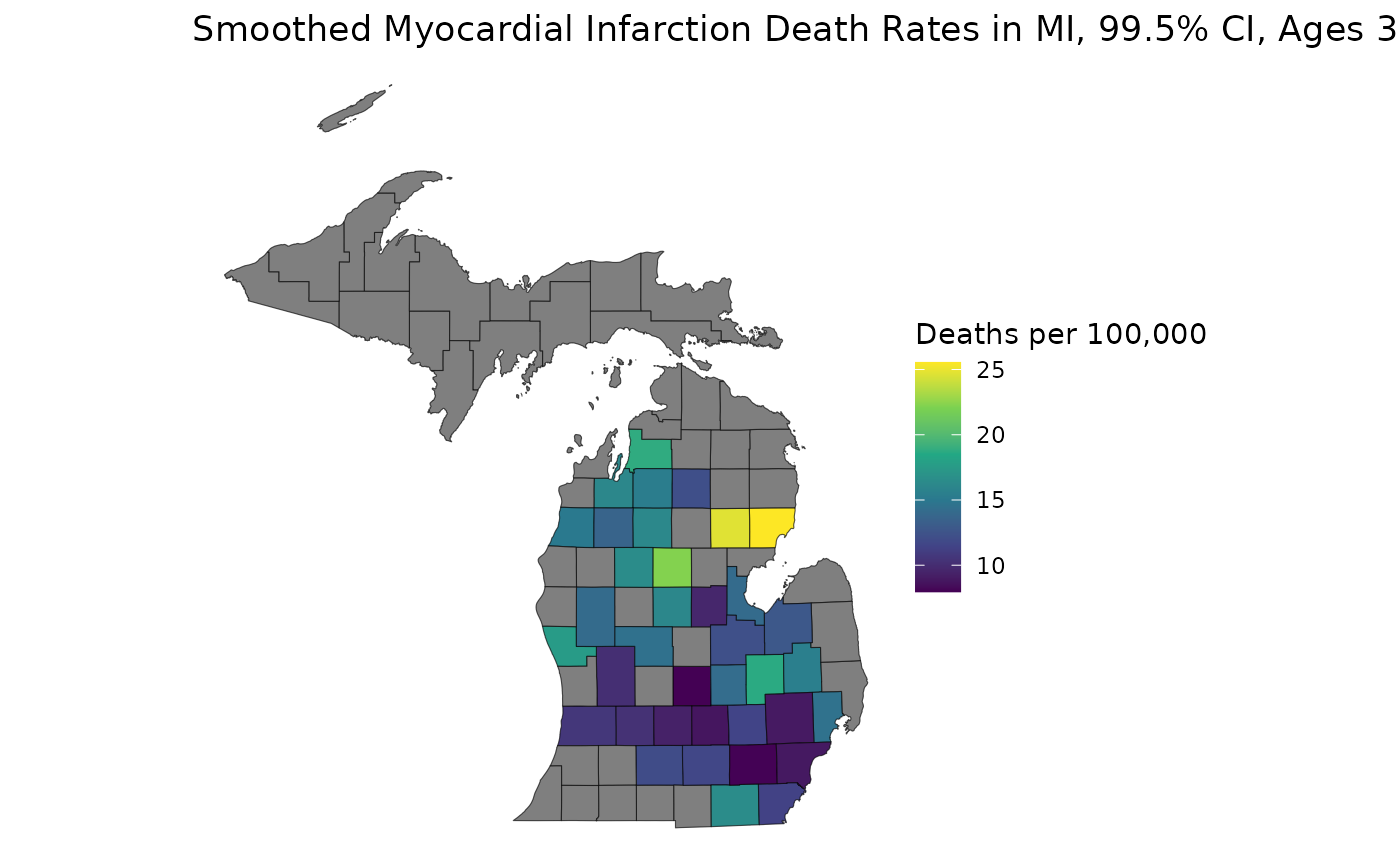

With our samples available, we can generate estimates from different credible intervals without having to re-run the model:

ci <- get_credible_interval(samples, 0.995)

rel_prec50 <- get_relative_precision(medians, ci)

low_rel_prec <- rel_prec50 < 1

medians_supp <- medians

medians_supp[low_rel_prec | low_population] <- NA

est_3544 <- medians_supp[, "35-44", "1988"]

ggplot(mishp) +

geom_sf(aes(fill = est_3544)) +

labs(

title = "Smoothed Myocardial Infarction Death Rates in MI, 99.5% CI, Ages 35-44, 1988",

fill = "Deaths per 100,000"

) +

scale_fill_viridis_c() +

theme_void()

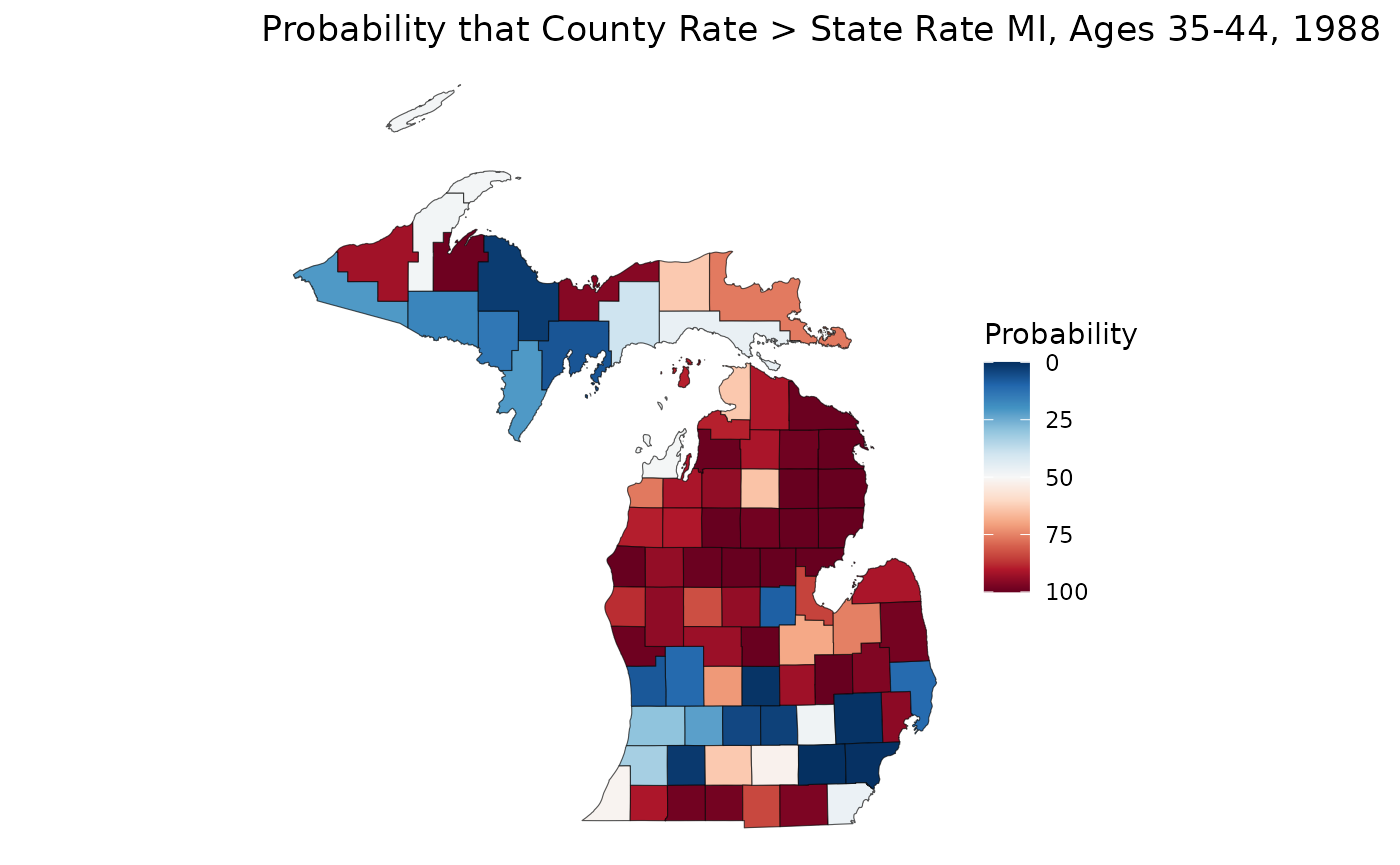

We can even use these samples to learn more about our data. Let’s say we are interested in figuring out if a rate estimate is statistically significantly greater than or less than the overall state rate. We can calculate a crude state rate for our 35-44 age group, then compare that against our samples. Note that we can make statistical significance comparisons, even if our rates are unreliable:

crude_3544 <- sum(mod_mst$data$Y[, "35-44", "1988"]) / sum(mod_mst$data$n[, "35-44", "1988"]) * 1e5

sample_3544 <- samples[, "35-44", "1988", ]

p_higher <- apply(sample_3544, 1, \(county) mean(county > crude_3544)) * 100

ggplot(mishp) +

geom_sf(aes(fill = p_higher)) +

labs(

title = "Probability that County Rate > State Rate MI, Ages 35-44, 1988",

fill = "Probability"

) +

scale_fill_continuous(palette = "RdBu", trans = "reverse") +

theme_void()

On this map, we can see that much of the northern Lower Peninsula is significantly lower than the state rate, whereas the southern portion of the LP has many places with significantly higher rates. The western Upper Peninsula also shows areas of significantly higher rates.

Closing Thoughts

In this vignette, we discussed features unique to sample processing

like aggregate_samples(), more granual control over our

samples, and extensions of our analysis using samples.